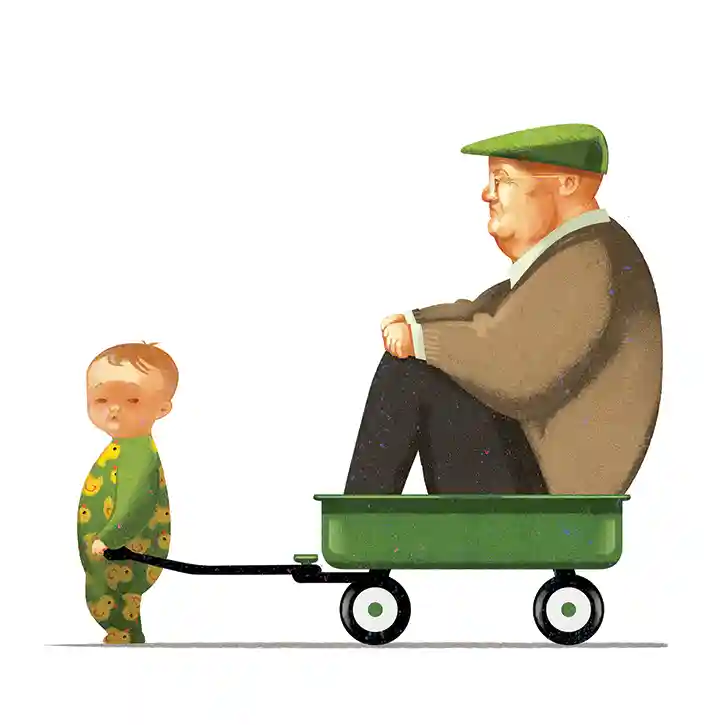

One of the most profound yet least understood and addressed changes—in the world and in most countries—is the demographic transition. It is relevant because it cuts across almost all economic, political, social, and cultural activities. It is poorly understood because its effects unfold over longer timeframes than other phenomena that tend to receive more attention: elections, wars, treaties, and economic crises.

Demographic transitions can refer to many things: fewer births (low fertility), population aging, and even population decline. To analyze them, it is worth starting with the commonly accepted model and then examining the current data for Mexico.

The demographic transition is a theoretical model developed by Warren Thompson1 nearly a hundred years ago, which describes the shift from high birth and death rates to low ones in a society over time. In its original form, the model identified four stages:

I) High birth and high death rates: the population remains stable with slow growth. II) Declining death rates: improvements in hygiene and medicine reduce mortality, especially among children, leading to a rapid population increase. III) Declining birth rates: with rising living standards, education, and access to contraception, birth rates begin to fall. IV) Low birth and death rates: both rates stabilize at low levels, and population growth slows or stabilizes.

That is a useful framework for understanding how population structures and socioeconomic dynamics change in the context of development and social modernization. Of course, it has its limitations and has sometimes been misunderstood.

For example, during stages II and III, the model predicts significant population growth, which has indeed occurred in most countries. In the 1970s, these population increases had a considerable influence on culture. A Malthusian logic prevailed, assuming that population growth would far exceed the availability of food, leading to widespread famines.2 However, some very different scenarios unfolded due to advances in food production around that time, which ushered in what would be stage IV—marked by lower birth rates and more stable populations.

What the model did not account for—and perhaps the most important demographic issue today—is a potential "stage V," in which very low birth rates (below replacement level) persist for extended periods. This phenomenon has become so powerful that it can dramatically alter societies.

To understand current discussions on demographic transitions, it’s essential to consider the importance of the total fertility rate (TFR) of 2.11.3 When a country has a TFR below 2.11 for a long period, its population will eventually begin to decline (excluding migration). A common mistake is to assume that population decline will happen immediately—but that’s not the case. Even in countries with steep drops in fertility, if there is still a large enough population in reproductive age, population growth can continue for some time. This is known as inertial growth.

What is striking is the number of countries that have fallen below replacement-level TFR, especially considering two key points. First, once a country crosses that threshold, it almost never returns to (or above) it.4 Second, public policies have had limited success in restoring fertility to replacement levels.5 Without attempting to be exhaustive, here are some notable facts about TFR:

- Some countries have had low TFRs for so many years that they are now experiencing population decline; Germany, Japan, and Russia are among the most representative.

- Spain, Italy, and Portugal maintained high fertility rates longer than Northern European countries. However, when their fertility rates fell, they dropped sharply—and now these countries have the lowest rates in the region.

- In almost all Asian countries, fertility is plummeting. There are extreme cases like South Korea, where a TFR of around 1 is pushing the country toward a “demographic trap” (population implosion).

- Africa is the only region in the world where nearly all countries still have high (even very high) TFRs.

- Latin America presents a particularly important case: almost all countries are undergoing a rapid demographic transition. That is, they are moving from stage III of the model—declining birth rates—to stage V—very low birth rates, below replacement level—with only a short period of stability in between. This has considerable implications for public policy.

How is the transition going in Mexico? The short answer is: like in almost all Latin American countries, it has accelerated significantly. The United Nations estimates that Mexico’s current TFR is around 1.8 and will remain stable at that level for a few years. However, when reviewing birth records and other data sources, it appears that Mexico’s fertility rate may actually be closer to 1.6. Until more definitive references emerge, let’s use the current UN projections—which, even if slightly overestimated, point to a sharp drop in TFR: nearly 0.4 points in just ten years.

Projections for Mexico’s total population indicate that it will be slightly below 150 million people around the year 2053. From that point on, the population will begin to decline. It is important to note that the arrival at—and descent from—this “zenith” will be slow. Mexico will remain near its population peak for a long time (around thirty years), with minimal variation from the maximum value.

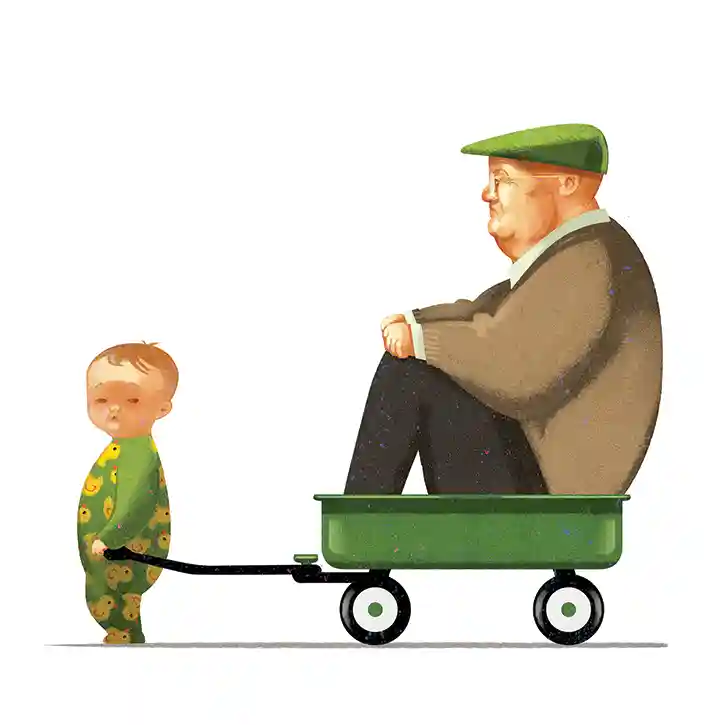

In my view, the most important demographic issue we will have to address in the coming years is not the population decline, but how the population will be restructured. A particular challenge is the 65+ age group, which will nearly triple between 2025 and 2050, reaching 20 % of the total population. Meanwhile, the population under 25 will steadily lose relative weight, dropping from the current 42% to around 30 % by 2050.

There are two major challenges to the demographic transition in the coming years. First, compared to other countries that have already gone through this process, the transition in Mexico will occur more rapidly. Second, it is happening while our per capita income is still relatively low. Now, adopting a catastrophic outlook is of little use—the real urgency is to plan ahead and adopt medium and long-term perspectives.

One of the greatest complications of the economic side of the transition is that political economy tends to favor the short term. Below, I outline five elements—non-exhaustive—where public policy, the private sector, and institutional development can contribute to a more orderly transition and improved well-being for the entire population.

1. A viable pension system: There is an urgent need for a legal framework to govern, at least in terms of public resources, a system as fragmented as Mexico’s. As life expectancy increases, people will need to work for more years. Two reforms have been enacted in recent years, in 2020 and 2024. Both strengthen the individual account system, which may prove highly beneficial in the long term.

However, two major unresolved issues remain (and likely more). First, we have a long transitional generation with entitlements under the old pay-as-you-go pension system. For at least the next several years, pension spending will continue to rise significantly, threatening to strangle the entire fiscal system.6 Analyzing what to do with this transitional generation is both complex and essential. Second, a large portion of the population works in the informal sector, making it urgent to ensure the financial viability of the non-contributory pension system, which is funded through general taxation.

2. Financing the health system: A demographic transition inevitably brings about an epidemiological transition. When a population is relatively young, communicable diseases are more prevalent. As the population ages, non-communicable chronic diseases (such as hypertension, kidney problems, cancers, etc.) become more dominant. These illnesses are extremely costly due to the complexity and length of their treatments. Financial planning is therefore critical.

The 2025 economic package paints a troubling picture. Efforts to reduce the fiscal deficit led to cuts in federal health spending, bringing it down to a very low 2.5 % of GDP. A significant increase in the health budget is indispensable.

3. The care economy: This could well become the major revolution in social policy in the 21st century. Changes in family structures, increased life expectancy, and a growing number of people living with cognitive and mental disorders could result in many older adults being left without support. Care must also extend to children and people with disabilities. In some circumstances, caring for a family member can be a personal tragedy. Gender disparities are common, with women disproportionately bearing the burden. The good news is that, if well-designed, a care system can generate positive externalities for the labor market, public finances, and the broader economy by female labor force expansion

4. Migration: A largely overlooked issue. Demographic shifts in Mexico and across the region are likely to produce complex migration dynamics, both within countries and across borders. As much as possible, it is in everyone’s interest that these processes occur in an orderly manner. Migration has intertwined impacts on pensions, healthcare, and caregiving systems.

5. Public investment in infrastructure: With limited fiscal space and growing social spending pressures due to population aging, public investment is at risk of collapsing. This damages potential growth and can lead to a vicious cycle. With older populations voting for increases in services and transfers, political economy works against investment. Developing appropriate financing mechanisms and ensuring intergenerational equity will be crucial.

Mexico’s demographic transition is irreversible—but it is not a tragedy. On the positive side, we still have a relatively young population, and while fertility is falling, it has not collapsed. In terms of demographics, Mexico is in a more favorable position than most developed economies and our Asian competitors.

On the challenge side, our low tax revenues and limited fiscal space greatly restrict the public policies we can pursue. It doesn’t help that political economy often works against long-term planning—costs are borne in the present, while benefits lie in the future, making delay the default response.

The next twenty years will not bring depopulation to Mexico. What we will see is population aging: fewer children and young people, and more older adults. Public finances will have to balance pressing social demands (pensions, health spending, and the care system) with the need for public infrastructure investment, vital for long-term growth and well-being. At the same time, it will be essential to regulate both international and internal migration, given its enormous potential to drive social transformation.

The greatest mistake is to ignore the demographic transition. Its influence on most of the things we consider important will be immense. The question remains whether our institutions are truly designed for the long term. What we do know for certain is that good planning can create an enormous difference in well-being for millions of people.

Héctor Juan Villarreal Páez

Research Professor at EGyTP and Leader of the Initiative for Economic and Demographic Transition (ITED) at Tecnológico de Monterrey.

1 Warren, T. “Population”, American Journal of Sociology, 34(6), 1929, pp. 959-975.

2 There were very radical opinions on this issue. Publications by the “Club of Rome” from that time can be consulted. There were also dystopian novels and films where overpopulation was a central theme—for example, Soylent Green.

3 Replacement must be higher than 2 due to children who die before reaching reproductive age, the slightly higher number of male births, and complications during childbirth. As infant and child mortality declines, the replacement level may get closer to 2.

4 A notable exception would be the United States in the 1980s, which experienced a significant increase in fertility. After the 2008 financial crisis, its fertility rate dropped to levels similar to those of Western Europe.

5 For a broader discussion on this topic, I recommend consulting: Doepke, M.; Hannusch, A.; Kindermann, F.; and Tertilt, M. “The Economics of Fertility: A New Era,” National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022.

6 CIEP in its document “Implications of the 2025 economic package” points out that spending on pensions, including non-contributory pensions, represents more than 40% of tax revenues.